Reveal Perspective: Creating Geospatial Data

Reveal Perspectives offers a closer look at our ideas, inspirations, and interests inside and outside the office. It’s where we share the viewpoints that drive our curiosity and shape how we understand the world. These stories reflect how we think, connect, and create meaning together through our work.

Creating Geospatial Data: Mason and Dixon and the Making of a Line

By Michael Ratcliffe

Given our day-to-day work with digital geospatial data, geographic information systems (GIS), and global positioning systems (GPS), the idea of physically delineating a boundary on the landscape, setting up surveying equipment, doing mathematical calculations by hand, and having a crew of workers felling trees, clearing brush, and installing stone markers seems, well, nothing short of phenomenal. As we celebrate World GIS Day, let’s step back from our computer screens and think about how geospatial information was created in the past. Specifically, the work of astronomer Charles Mason and surveyor Jeremiah Dixon. It’s a story about bringing science and technology as well as careful planning to bear to produce accurate geospatial information and resolve a real-world problem.

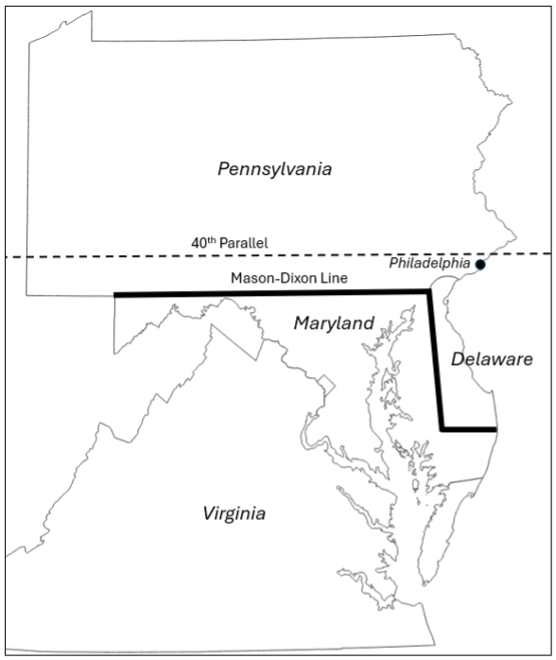

Mason and Dixon (and a crew of workers providing support) surveyed their eponymous line between 1763 and 1767 to settle the long-standing dispute between the Calvert and Penn families over the location of the boundary between Maryland, on the one hand, and Pennsylvania and Delaware, on the other. At the time, Delaware was a satellite colony of Pennsylvania. The Calvert’s 1632 charter for Maryland put the colony’s northern boundary on the 40th parallel (Figure 1). Unfortunately, the 1681 grant to William Penn referenced an inaccurate map and depicted Pennsylvania’s southern boundary farther south than it really was. To complicate things, Penn’s selection for the location of Philadelphia, based on the map, was south of the 40th parallel. Clearly, a fix was needed.

Figure 1. The Geographical Context of the Mason-Dixon Line. Source: Produced by author. Cartographic boundary files from U.S. Census Bureau.

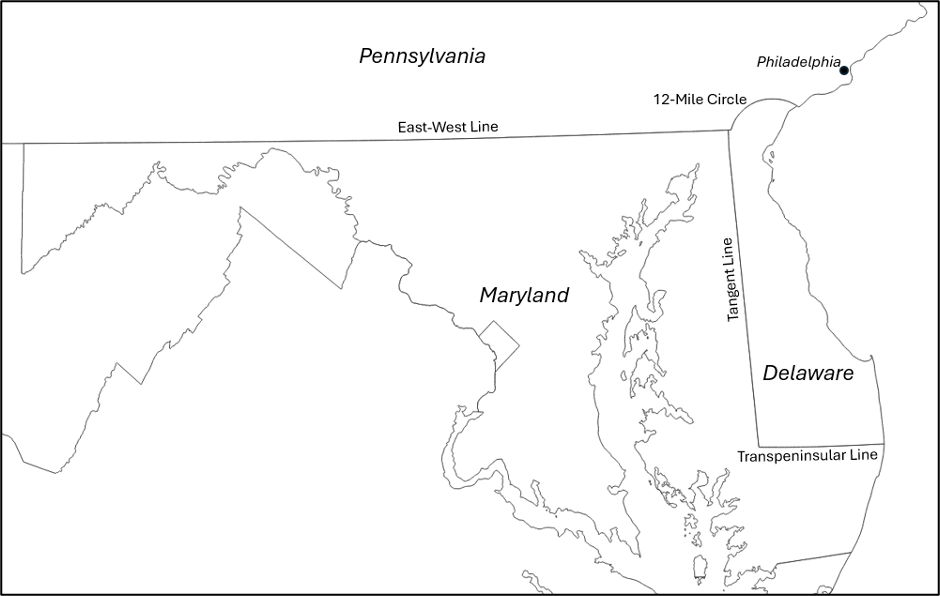

The boundary dispute simmered for decades (though it should be noted that people living in the disputed area took advantage of the geographical uncertainty whenever tax collectors showed up). Eventually both sides agreed that the east-west boundary between the two colonies would follow the line of latitude 15 miles south of the southernmost house in Philadelphia (the importance of accurate mapping of residential locations!), starting at the western arc of a 12-mile circle centered on the courthouse in New Castle, Delaware. The boundary between Maryland and Delaware followed a line running westward from the Atlantic to the Chesapeake and northward from the midpoint of the “Transpeninsular Line,” touching the 12-mile circle at a tangent. The survey utilized state-of-the-art equipment (for the time) and required astronomical readings and advanced mathematics to ensure accuracy. The operation also required careful project planning. The surveyors couldn’t simply start at a point and continue onward. They had to establish the proper sequence in which to establish the 12-mile arc, identify the tangent point and line, confirm the Transpeninsular Line’s midpoint, survey the line bisecting the Delmarva Peninsula, and survey the east-west line. In other words, identifying the project’s literal critical path. It was an extraordinary undertaking, to say the least.

Figure 2. Components of Mason and Dixon’s Line. Source: Produced by author. Cartographic boundary files from US Census Bureau.

The survey crew placed stone markers at one-mile intervals. Milestones were marked with an M on the Maryland side and a P on the Pennsylvania side. Every fifth stone was a crownstone, marked with the Calvert family crest on one side and the Penn family crest on the other (Figure 3). Many of these stones can still be found along the length of the boundary, though after nearly 260 years many are worn or damaged (Figure 4). Thanks to the work of the Mason and Dixon Line Preservation Partnership, the Maryland Geological Survey, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, and others, including owners of properties on which the stones are located, many of the markers have been georeferenced, and to the extent possible, protected and restored. See https://www.mdlpp.org/ for more information, and head out and see these monuments to geospatial information for yourself!

Figure 3. Crownstone/mile marker #50, southwest of New Freedom, Pennsylvania: Calvert family crest visible in photo on left; Penn family crest visible in photo on right. Source: Mason and Dixon Line Preservation Partnership.

Figure 4. Mile marker #84, Carroll Valley, Pennsylvania, west of Emmitsburg, Maryland. Photo by author, with thanks to the owners of the property where the marker is located.